Thoughts on J

I’ve been writing the J programming language regularly since roughly June 2022, so I thought I’d write a blog post about my experience with it so far. Originally, I wrote this post all the way back in July 2022. It is now… May 2023. Oops.

Better late than never!

As a heads-up warning, this post has ended up being quite long. It might take a long time to read (say, 60–75 minutes) and digest (depends how much you grok the array language concepts).

For the most part, J has been a great language with a lot of cool innovations compared to paradigms I’ve worked with before. I do have some gripes with the language as well, which I’ll talk about too. Finally, I’ll cover some of the changes I would make to an array language like J if I were designing my own.

This article contains some moderately complex J code. It isn’t too important to understand to get the points in the article—feel free to skim over it as it comes up. I’ve provided surface-level explanations but refrained from digressing too far to fully explore the way the code works.

If you want to follow along with any of the examples, you may find the following useful:

NuVoc, the glossary of J vocabulary

J download, for installing yourself

J online, to just try out small snippets—follow along!

Why did I start writing J?

Learning an array language had been on my mind since roughly late 2020 to early 2021. The novelty of the paradigm was intriguing, and the idea of having a large number of primitives to perform what would be standard library functions or left to the programmer to implement was interesting.

The first array language I met was APL.

Without going into a detailed history, APL is the ancestor of modern array languages (and libraries, like NumPy).

APL is alien.

It’s exotic.

It looks like this: {↑1 ⍵∨.∧3 4=+/,¯1 0 1∘.⊖¯1 0 1∘.⌽⊂⍵} (which implements a single step of Conway’s game of life, written by John Scholes!).

The allure of the strange character set and array operations was undeniable. I also found a lot of the example programs very elegant with explanations. However, I didn’t really want to go through the relative pain of learning an alternate keymap or shortcuts. J’s ASCII ended up being simpler for me to learn while still offering a good experience with array languages. At some point, I may learn an array language that uses an atypical character set (most probably BQN). Until then, J will remain my array language of choice.

J has served well as a calculator/spreadsheet drop-in. A lot of numerical questions can be answered quickly with the J terminal open. It’s also a great quick distraction when I want to think about solving some tiny problem for a bit when I need a break. Problem sites like LeetCode or Project Euler have no shortage of quick programming puzzles to solve. For longer problems, Advent of Code also offers a good selection of challenges. I tweet the random snippets of J I write fairly frequently; those are examples of the kind of quick code I write.

A note on vocabulary

The vocabulary used by J is quite different to most languages. The concepts are generally fairly analogous to more common terms, but I will explain the J-specific terminology here.

Things in J are named after parts of speech. This is because there are similarities between their linguistic counterparts and how the J constructs behave. Rather than invent new terms, existing ones are borrowed.

Data in J is called a noun. Other languages might use a term like “value” or “variable” to refer to a similar concept. Just as in linguistics, nouns in J are “things”.

A noun can be either an atom (single value) or an array (a collection of atoms). All nouns also have a noun rank (number of dimensions it has), a shape (the length of each dimension), and a datatype. There are various datatypes, such as integral, boolean, floating point, ASCII character, Unicode character, and so forth.

Some example nouns:

NB. The literal number 1 - an atom

1

1

NB. The array of 1, 2, and 3 - an array

1 2 3

1 2 3

NB. A string

'Ibzan'

Ibzan

Verbs are similar to functions in other languages, or in mathematics. They are the words that manipulate nouns by doing something to them.

Verbs have a valence, which is how many arguments they take. In J, there are only two options: monadic (unary, one argument) and dyadic (binary, two arguments). This is because the syntax only allows for a verb to take up to two arguments—one to the left, and one to the right. J does not have function calls with brackets like other languages. Everything is either prefix or infix, based on its valence.

Verbs also have a verb rank, which influences how they operate on nouns, and I will talk about at various points of the post.

Some example verbs:

NB. Addition

1 + 2

3

NB. Unary negation - monadic -

- 1

_1

NB. J uses the underscore for the minus sign in numeric literals

NB. Subtraction - dyadic -

5 - 3

2

NB. As mentioned, J has more primitives than most languages

NB. *: squares a number

*: 4

16

Modifiers in J are similar to higher-order functions in other languages. They take either one or two operands and produce a verb. Modifiers that take one operand are called adverbs, and modifiers that take two are called conjunctions.

Some example modifiers:

NB. / insert, which puts the verb it modifies between elements of an array

+/ 1 2 3

6

NB. This is equivalent to:

1 + 2 + 3

6

NB. @: at, which is function composition

NB. add then square

5 *: @: + 3

64

Finally, to round out the six parts of speech J uses, there are two relatively uninteresting parts.

Copula is the name given to the assignment operators in J, =. is (local) and =: is (global).

Control words are used for program flow in more typical imperative fashion, such as if. do. end. .

I won’t be covering control words here, since they aren’t relevant to most J code I write.

Not usually classed as a part of speech, J refers to quotes, brackets (parentheses), and comment markers as punctuation. Quotes demarcate strings, brackets control execution order, and comment markers indicate the start of a comment.

Rank

Rank is an important concept in J—by which I mean both noun rank and verb rank. The rank of a noun and a verb operating on it is responsible for lots of behaviour, similar to nested loops in imperative languages.

To understand noun rank better, it may be useful to build up higher rank nouns inductively. A rank 0 noun is an atom—a single value.

1

1

We can see the rank by using the $ shape of verb on a noun.

$ 1

The empty return value shows that this is an atom. In fact, the return value of shape of is always a list, even if it is empty or contains a single item. A list is the name for a rank-1 array in J, and is built out of a sequence of rank-0 items; atoms. An example list would be:

1 2 3 4 5

1 2 3 4 5

$ 1 2 3 4 5

5

The shape of this list is 5 —it contains five items in a single axis.

Just as a list is a sequence of atoms, a table (rank 2 array) is a sequence of lists of the same length.

We can build a table with verbs like i. integers, dyadic $ shape, or ,: laminate.

NB. i. integers produces an array with the specified shape

i. 5

0 1 2 3 4

$ i. 5

5

NB. A 2 by 3 table

i. 2 3

0 1 2

3 4 5

$ i. 2 3

2 3

NB. $ takes an existing array and reshapes it

2 3 $ 10 20 30 40 50 60

10 20 30

40 50 60

NB. See here how the resulting shape is specified on the left

NB. ,: combines two arrays to make two rows of a table

100 200 300 ,: 400 500 600

100 200 300

400 500 600

Theoretically, there is no upper bound to the rank of a noun. We can make a rank 3 noun, sometimes called a brick, from a collection of tables all with the same shape, and a rank 4 noun from those, and so on and so forth. More realistically, the increasing number of dimensions means larger and larger arrays consume more and more memory.

Verb rank controls how a verb dices up an array to broadcast operations across it. I cover this in more detail in a later section.

The things I like

These features are presented in roughly decreasing order of relevance, but it’s not a hard-and-fast ranking. I’ve listed things that I think are unique to J from a non-array perspective, or perhaps even to J within other array languages.

Diverse collection of primitives

Most language have a few basic operations that the user can construct more advanced expressions from. Commonly available operators include:

+,-,*,/elementary arithmetic: addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division%modular arithmetic<,>,<=,>=,==,!=comparison operators&&,||,!logical AND, OR, and NOT&,|,^,<<,>>,~bitwise AND, OR, XOR, left shift, right shift, and complement

This is obviously not an exhaustive list.

J, however, has a far larger complement of primitives.

By overloading a given verb based on whether it is used monadically or dyadically, J allows for a high density of operations in a relatively small space.

These primitives can be viewed on the wiki’s NuVoc page.

Primitives are typically made of one or two characters (although some have three), of which there is a “root” character and an “inflection” in the form of a dot . or colon : .

While the inflection is purely cosmetic, and the primitive doesn’t have to be related to the root, a lot of J primitives are.

For example, + is plus and +: is double.

Similarly, - is minus and -: is halve, * is times and *: is square, % is divide and %: is square root.

This helps learning primitives by making related effects have related representations.

Having access to all these primitives allows for terse code. Sometimes terseness is viewed as a negative, but I believe there is an appropriate level of it—verbosity can be equally painful to follow. It also aids writing in a point-free style (typically called tacit within array languages). This is in itself especially useful when dealing with modifier trains.

Compared to APL or BQN, J’s ASCII primitives can be harder to read, since many of them are digraphs consisting of a character and either . or : .

In languages with distinct glyphs for each operator is more visually distinctive, which aids recognition.

It also makes easier to write by hand, for the few people who do.

However, I think this makes it vastly easier to write on a keyboard. Each primitive is self-evident in how it can be typed on any keyboard layout that supports ASCII characters.

An interesting compromise may be to create a font that uses ligatures to combine the J di- and trigraphs into a single displayed character, while still treating them as separate objects for the interpreter. An issue with this in J would be dealing with the difference between monadic and dyadic uses of a primitive, but I suspect they would just have to share the visual representation. I do not currently use this approach, instead leaving the visual representation of the primitives alone.

When reading J (or any array language), there is definitely an ideal length for terse fragments.

Common patterns like (arithmetic) mean +/%# (which is made of + plus, / insert, % divide, and # tally in a fork) are perfectly reasonable to read.

On the other hand,

]`(97&([ + 26 | 13 + -~))`(65&([ + 26 | 13 + -~))@.((([ ([ >: [: a.&i. ]) [: {. ]) *. [ ([ <: [: a.&i. ]) [: {: ])&'az' + 2 * (([ ([ >: [: a.&i. ]) [: {. ]) *. [ ([ <: [: a.&i. ]) [: {: ])&'AZ')&.:(a.&i.)

is just too long.

A later version of this was shorter:

]`(65&([ + 26 | 13 + -~))`(97&([ + 26 | 13 + -~))@.(64 91 96 123 >.@:-:@:I. a. i. ])&.:(a.&i.)

but it still too long to easily parse.

When separated out into parts that each perform a specific role, it becomes more manageable. I shan’t go too deep into explaining this implementation since it isn’t the purpose of the article, but a brief explanation is included.

NB. Determine whether we are mapping an upper case letter,

NB. lower case letter, or nothing at all.

NB. 0 = nothing

NB. 1 = upper case

NB. 2 = lower case

regime =. (((_1 1 $~ #) + a. i. ]) 'AZaz') >.@:-:@:I. ]

NB. Perform the fundamental rot13 operation: subtract an offset,

NB. add 13, modulo 26, then add the offset back.

NB. The offset is necessary to account for treating ASCII characters as numbers

NB. ranging from 0-255.

rot13lim =. [ + 26 | 13 + -~

NB. Versions of the above for lower and upper case

mapLower =. (a.i.'a')&rot13lim

mapUpper =. (a.i.'A')&rot13lim

NB. Gerund + agenda to dispatch the appropriate verb

NB. Using ] same to leave non-letters alone

map =. ]`mapUpper`mapLower@.regime

NB. Convert to/from characters using &. and map the numbers

rot13 =: map&.(a.&i.)

NuVoc links: $ shape, ~ passive, # tally, + plus, a. alphabet, i. index of, ] same, >. ceiling, @: at, -: halve, I. indices, [ left, | residue, & bond, ` tie, @. agenda, and &. under (dual).

I consider this to be a decent compromise between brevity and verbosity. The individual verbs are simple enough to be understood separately, and the names communicate the overall function of each verb to the later parts. However, it is also a demonstration of the difficulty of reading J from a beginner perspective: even this short example is extremely dense.

JQt as a notepad

One of the IDEs that comes from J’s package manager is JQt. The feature I like best about JQt is its terminal, which I have found great for interactive development.

The main feature of JQt that most other REPLs don’t have is a mutable history. JQt allows the user to treat the entire page as editable. You can go to a previous line and edit or delete it if desired. Deletion is the main thing I use this for—removing a lengthy output or failed solution from the page to keep it clean. I also often prepare gists in the terminal, since it allows for writing text in comments alongside actually running code easily.

The ability to edit history is a double-edged sword. It is possible for the user to edit the output or a prompt in a way that is misleading later. So far this hasn’t bitten me, and J does keep a separate log of inputs, but it is a potential issue.

An improvement here could be to basically copy the way a Jupyter notebook handles it—by having cells. In fact, there is a way to run J inside a Jupyter notebook. I have played around with it a bit, but I haven’t switched to using it full-time. Ultimately, by allowing the user to remove or replace bits of history that aren’t useful, but not letting them edit the output directly, the most sensible balance is probably struck.

JQt also comes with in-built support for debugging, running snippets, project management, as one would expect from an IDE, although it is a bit less clear than other IDEs. This is all useful stuff one would (and should, from a serious language) expect nowadays, and the best part is definitely the interactive terminal—especially the deletable history—in my opinion.

^: Power of verb conjunction

Sometimes you come across a language feature that is truly magical.

^: is one of those features.

It is the power of verb conjunction, which has the ability to raise a verb to some power.

What does that mean?

A basic example is repeating an operation for a fixed number of times.

i. 5

0 1 2 3 4

NB. *: is square

*: i. 5

0 1 4 9 16

NB. Square twice using *: *:

*: *: i. 5

0 1 16 81 256

NB. Square twice using ^:

*:^:2 i. 5

0 1 16 81 256

NuVoc links: *: square, i. integers.

Zero and one are also both numbers, which can be used to create a construct similar to if in other languages.

A verb to the power of zero has the analogy of a number to the power of zero equalling one—in this case, doing nothing.

n =: 2

*:^:(n >: 5) n

2

n =: 10

*:^:(n >: 5) n

100

NuVoc links: *: square, >: greater than or equal to.

That’s pretty cool!

This is only scratching the surface of ^: .

It has another feature: it can perform the inverse operation of a given verb, too!

NB. %: is square root

%: i. 5

0 1 1.41421 1.73205 2

NB. Square root using ^:

*:^:_1 i. 5

0 1 1.41421 1.73205 2

NuVoc links: %: square root, i. integers.

The inverse is also worked out for verbs that are made out of existing verbs with inverses.

NB. The running total

] xs =: +/\ 2 1 3 5 3 1 1

2 3 6 11 14 15 16

NB. The inverse of the running totals

+/\^:_1 xs

2 1 3 5 3 1 1

NB. The inverse can be inspected using b. _1

+/\ b. _1

(- |.!.0) :.(+/\)

Strictly speaking, J calls this operation the obverse, not the inverse. The difference is that the obverse can be manually assigned to be something else (but it is the inverse by default for supported primitives).

NuVoc links: + plus, / insert, \ prefix. - minus, b. verb info |.!.n shift, :. assign obverse.

^: can be used with _ infinity to repeat a verb until it converges.

Extremely useful when you want to find an end state of a convergent operation.

I’ve frequently used ^:_ for implementing algorithms like flood fill, which stop when reaching a convergent state.

A simpler example is the Collatz conjecture:

NB. Perform one step of the Collatz conjecture iteration.

NB. Don't worry too much about the implementation, but the primitives are linked below.

collatz =: -:`(>:@(3&*))`1: @. (1&= + 2&|)

collatz^:_ (19)

1

NB. Yes, it converges (to 1).

Furthermore, J can collect the intermediate results into an array by using a: ace (boxed empty):

collatz^:a: 19

19 58 29 88 44 22 11 34 17 52 26 13 40 20 10 5 16 8 4 2 1

NuVoc links: -: halve, >: increment, @ atop, & bond, * times, 1: constant functions, ` gerunds, @. agenda, = equals, + plus, | residue.

If the exponent is an array, then ^: will raise the verb to each value in the array.

This is useful for repeating an operation a set number of times when you want to retain the intermediate results.

NB. Tetration, using J's right-to-left order of operation

2^^:(i. 4) 2

2 4 16 65536

NB. To help understand tetration, this could alternately be calculated like this:

|. ^/\. 4 $ 2

2 4 16 65536

NuVoc links: ^ power, i. integers, |. reverse, / insert, \. suffix, $ shape.

So far, ^: has only been used with a fixed value for the power—either a number, or another noun like _ or a: .

^: also supports a dynamic application, where the power is determined by a verb.

Instead of the “power” being a noun (value), it can also be a verb (function).

This has two main applications: a dynamic if , and a do while construct, which are familiar from procedural languages.

NB. Dynamic if - ^: with a function

NB. Double if greater than 5

+:^:(5&<)"0 i. 10

0 1 2 3 4 5 12 14 16 18

NB. Do-while - ^: with a function and also ^:_

NB. Double while less than 1024

+:^:(<&1024)^:_ (23)

1472

NuVoc links: +: double, & bond, < less than, " rank, i. integers.

Modifier trains

Modifier trains are one of J’s approaches to combining functions.

J does have a more typical approach with a family of conjunctions ( @ atop, @: at, & compose, &: appose) with varying semantics involving rank.

For certain classes of problems the two main modifier trains, hooks and forks, which deal with combining verbs to make another verb.

Forks and hooks can be difficult to read at first since they are effectively invisible, but they become easier to read with experience.

When used monadically, forks may be familiar as the S′ combinator, and hooks as the S combinator.

A fork is made of two monads (or dyads), and a dyad.

The two verbs either side process the input arguments, and then the middle dyad combines their results.

In other words, (f g h) y is equivalent to (f y) g (h y) , and x (f g h) y is equivalent to (x f y) g (x h y) .

The wiki uses this image (on the fork page) to explain a fork, with square brackets represented the optional x argument:

result

|

g

/ \

/ \

/ \

f h

[/]\ [/]\

[x] y [x] y

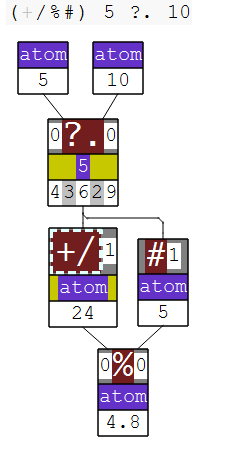

My favourite example of a fork is the (arithmetic) mean, and can be developed bit-by-bit as follows:

NB. An array of random numbers (using a fixed seed):

5 ?. 10

4 3 6 2 9

NB. The mean is defined as the sum of the elements divided by the count.

NB. Summing can be done using +/

+/ 5 ?. 10

24

NB. And the count is given by #

# 5 ?. 10

5

NB. J uses % for division.

NB. Here's an explicit definition of the mean

mean =: {{ (+/ y) % (# y) }}

mean 5 ?. 10

4.8

NB. Feel free to check this on a calculator.

NB. Note that in the definition, y appears on the right of both +/ and #

NB. +/ and # are both monadic verbs acting on y

NB. % is a dyadic verb acting on the outputs of +/ and #

NB. A fork can be used to replace this construct:

mean =: {{ (+/ % #) y }}

mean 5 ?. 10

4.8

NB. Since y only appears once and on the right, deleted to make the verb tacit:

mean =: (+/%#)

mean 5 ?. 10

4.8

NuVoc links: ?. roll, + plus, / insert, # tally, % divide.

This is, of course, a rather simple example. A lot of code follows the basic pattern of having two monads with a dyad to combine the result. Forks within forks are also useful—one of the monadic verbs of a (monadic) fork can itself be a fork.

Hooks are made of a pair of verbs: a monad, and a dyad.

The monad “pre-processes” one argument, and then the dyad combines its result with either the other input argument (in the dyadic case), or the unmodified input (in the monadic case).

That is to say, (v u) y is equivalent to y v u y , and x (v u) y is equivalent to x v u y .

As with the fork, the hook page has a diagram:

result

|

u

/ \

x or y v

|

y

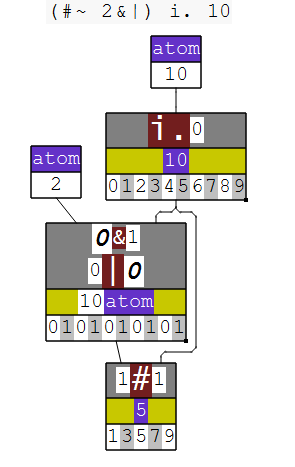

A very simple example of a hook is a filter made of the verb #~ and a verb to convert the input into a mask of 0s and 1s.

For example, to extract odd numbers from an array:

i. 10

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

2 | i. 10

0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1

(2 | i. 10) # i. 10

1 3 5 7 9

(i. 10) #~ 2 | i. 10

1 3 5 7 9

(#~ 2&|) i. 10

1 3 5 7 9

NuVoc links: i. integers, | residue, # copy, ~ passive, & bond.

Here, (#~ 2&|) is the hook, made of two composite verbs.

#~ acts as a filter, with the right-hand argument being the mask and the left-hand argument being the thing to filter.

2&| finds the remainder modulo 2—1 for odd numbers, 0 for evens.

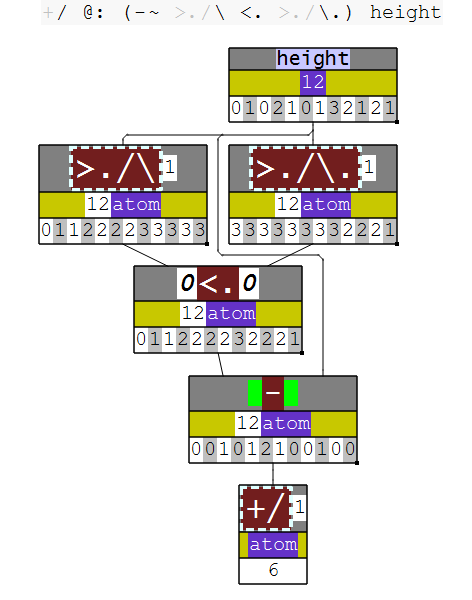

It is possible to write longer modifier trains, too. In my experience they get quite hard to read though. A 4-train is not too hard to read though, such as this solution to LeetCode problem 42:

+/ @: (-~ >./\ <. >./\.)

NuVoc links: + plus, / insert, @: at, - minus, ~ passive, >. max, \ prefix, <. min, \. suffix.

Here, (-~ >./\ <. >./\.) is a 4-train made of a fork >./\ <. >./\. and then that fork is the right-hand verb in a hook, with -~ .

While useful in this case, the longer and longer a train gets the harder it can be for humans to parse.

The rule of thumb is that everything in J comes in groups of two or three.

height =: 0 1 0 2 1 0 1 3 2 1 2 1

+/ @: (-~ >./\ <. >./\.) height

6

These diagrams were made by dissect, which I talk about later.

J’s adverbs

Modifiers are equivalent to higher-order functions in other languages. They are primitives that come in two forms: adverbs and conjunctions.

Conjunctions take two inputs, such as a verb and a noun or two verbs and produce a new part of speech, like a verb. Useful conjunctions include:

the six composition conjunctions

@atop,@:at,&compose,&:appose,&.under (dual), and&.:underperhaps most of all,

"rank

These conjunctions allow for combining verbs or modifying them in a variety of ways. However, I find that J’s adverbs are especially expressive.

Adverbs are what J calls modifiers that only take a single operand. While there aren’t many of them, they are extremely useful.

Perhaps the most common adverb is ~ as both reflex and passive.

Reflex is the monadic case, and passive is the dyadic one.

Reflex copies its input to both arguments of the verb it modifies, also known as the W combinator (elementary duplicator).

NB. An implementation of double

+~ 5

10

NuVoc links: + plus.

Passive is the more common of the two and flips the arguments of the verb (the F combinator). It is frequently used with verbs whose arguments can be swapped to make a tacit definition easier to write.

i. 10

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

2 | i. 10

0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1

(2 | i. 10) { i. 10

0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1

({~ 2&|) i. 10

0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1

NuVoc links: i. integers, | residue, { from, & bond.

This particular usage ( {~ ) is extremely common in hooks like this one, since the modified value is passed on the right-hand side.

The other adverbs that are constantly cropping up are / insert and table, \ prefix and infix, and \. suffix.

All of these adverbs take the verb they modify and apply it to an array in some way or another.

NB. Insert inserts the verb between elements.

1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + 5

15

+/ 1 2 3 4 5

15

NB. Prefix applies the verb to successive prefixes.

NB. < creates boxes, letting us see the prefixes

<\ 1 2 3 4 5

┌─┬───┬─────┬───────┬─────────┐

│1│1 2│1 2 3│1 2 3 4│1 2 3 4 5│

└─┴───┴─────┴───────┴─────────┘

NB. +/ is itself a verb and can be used in an adverb.

+/\ 1 2 3 4 5

1 3 6 10 15

NB. This is the running total from earlier.

NB. Similarly, \. applies the verb to successive suffixes.

<\. 1 2 3 4 5

┌─────────┬───────┬─────┬───┬─┐

│1 2 3 4 5│2 3 4 5│3 4 5│4 5│5│

└─────────┴───────┴─────┴───┴─┘

+/\. 1 2 3 4 5

15 14 12 9 5

NB. Infix applies the verb to sliding windows of the given size.

2 <\ 1 2 3 4 5

┌───┬───┬───┬───┐

│1 2│2 3│3 4│4 5│

└───┴───┴───┴───┘

2 +/\ 1 2 3 4 5

3 5 7 9

NB. Table applies the verb to all pairs.

NB. Using ~ reflex here to provide the same argument to both inputs.

+/~ 1 2 3 4 5

2 3 4 5 6

3 4 5 6 7

4 5 6 7 8

5 6 7 8 9

6 7 8 9 10

These adverbs allow you to slice up an input array in many useful ways.

The others that I haven’t gone into detail about are /. oblique and key, and \. outfix

Oblique operates on diagonals of a table, key groups identical items (so #/. counts unique items via # tally), and \. outfix removes a sliding window from the array.

If these adverbs don’t offer sufficient ability to divide up the array, ;. cut almost certainly does.

While it technically a conjunction, the moment it gets a numeric code it becomes an adverb.

Cut is a collection of three adverbs.

Between them they can extract subarrays, split up an array into groups specified by a mask, and apply a verb to tiles of an array.

They also have the added benefit of being fairly efficient in terms of performance, although I have not yet had any issues with that in general with J.

Dissect

One of the addons in the J package manager is called debug/dissect .

It is one of the best debugging and explanation tools I have encountered in a language.

When writing a language as dense as J, it can be hard to fully understand how data is being passed around between verbs.

This is where dissect can help.

After loading the addon into your J session ( require 'debug/dissect' ), you are given access to a new verb dissect that takes a single argument—a string of a J sentence that produces a noun result.

If the sentence does not produce a noun, dissect cannot display it; it only tracks how data flows throughout the snippet from starting inputs to a final output.

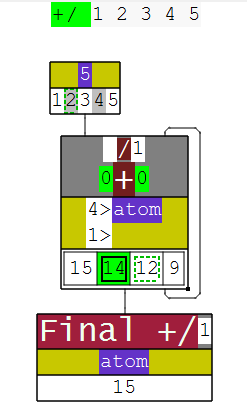

Dissect was used to generate the diagrams in earlier sections—but it also allows you to interrogate the steps further.

For example, in this dissection of +/ 1 2 3 4 5 , dissect can show the intermediate results of +/ .

The cell with a solid border and highlight ( 14 ) shows the value being probed, and the dashed borders of 12 and 2 (in the input) show the operands used to produce it.

I have found dissect to be an easy way to explain longer phrases to other people. The visual approach can really help communicate things like forks and hooks easier than quoting the definition.

Cyclic gerunds

In J, a gerund is a collection of verbs (sort of—it’s more complicated, but for now this explanation will suffice).

Gerunds have several different uses within J, such as allowing for dispatching a different verb based on some condition (see @. agenda).

One of these uses is to alternately apply the different verbs it represents.

For example, to alternate addition and subtraction over a list:

i. 10

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

+`-/ i. 10

9

0 + 1 - 2 + 3 - 4 + 5 - 6 + 7 - 8 + 9

9

Another example is when combined with the " rank conjunction to instruct the gerund to act as a verb:

(+:`-:)"0 i. 10

0 0.5 4 1.5 8 2.5 12 3.5 16 4.5

NuVoc links: +: double, -: halve.

Here, the verb is acting on rank 0—the individual atoms of the input array. Then, the gerund cycles through its elements to apply the given verb to each of those cells. This works for any given rank:

i. 2 2

0 1

2 3

(+:`-:)"1 i. 2 2

0 2

1 1.5

i. 2 2 2 2

0 1

2 3

4 5

6 7

8 9

10 11

12 13

14 15

(+:`-:)"2 i. 2 2 2 2

0 2

4 6

2 2.5

3 3.5

16 18

20 22

6 6.5

7 7.5

The main application I have found of cyclic gerunds is when dealing with heterogenous data in a boxed array. In this sense, heterogenous may mean different in what it represents as opposed to what datatype it is represented by. In the following example, each string is alternately converted to upper or lower case.

] words =. ;: 'Some example text. Some more example text.'

┌────┬───────┬─────┬────┬────┬───────┬─────┐

│Some│example│text.│Some│more│example│text.│

└────┴───────┴─────┴────┴────┴───────┴─────┘

(toupper each)`(tolower each)"0 words

┌────┬───────┬─────┬────┬────┬───────┬─────┐

│SOME│example│TEXT.│some│MORE│example│TEXT.│

└────┴───────┴─────┴────┴────┴───────┴─────┘

This is a relatively simple example but shows the versatility of a cyclic gerund for dealing with textual data.

For an array of boxed strings, each atom is a boxed string.

A more realistic use case would be using rxcut to split some input text into matching and non-matching boxes.

A cyclic gerund can then apply one verb to each match, and a different verb to the non-matches without being restricted to solely textual manipulations as using rxapply would be.

Leading axis model and rank

The leading axis model (also called leading axis theory) is made of two main parts.

The first is that arrays are manipulated by turning them into cells of the necessary rank and then giving those to the verbs.

For example, (dyadic) + plus has rank 0 0.

This means that to add two arrays together, they must first both be reduced all the way to 0-cells (atoms) and then added together.

Many other operators have rank _ (infinity), which means they work on the array as a whole.

On the other hand, some verbs don’t change with different rank.

For example +: double has to double each element in its input regardless of what rank it is modified to work on.

The second is that verbs act on the first axis of an array implicitly, or can be configured to use a later axis using the " rank operator.

This adds a level of consistency to the language, which makes it easier to read and write.

The rank operator also provides the motivation for making verbs act on the first axis: it becomes trivial to have the verb act on any later axis in the array.

The ability to specify what cells of an array a verb acts on are how J allows the programmer to avoid writing explicit loops and still get fine-grained control over effects.

J was designed from the ground up with the leading axis model in mind (unlike both SHARP and Dyalog APL, which had it retrofitted on). As a result, all of J’s primitives are designed with the leading axis model in mind—rank one functions all operate on the first axis, for example. This leads to many array operations being intuitive in J (at least in my experience).

i. 3 6

0 1 2 3 4 5

6 7 8 9 10 11

12 13 14 15 16 17

NB. This has shape 3 6, as specified

+/ i. 3 6

18 21 24 27 30 33

NB. This has summed up the columns, giving a result of shape 6

NB. which the same as the last axis from before

NB. If needed, we can sum rows instead:

+/"1 i. 3 6

15 51 87

NB. Here the rank modifier creates a new verb that

NB. acts on the 1-cells (rows) of the array.

NB. The result is of shape 3 - the first axis.

NuVoc links: + plus, / insert.

Furthermore, J’s ability to broadcast arrays is underpinned by a concept called agreement; two arrays agree if they share a prefix of their shapes (for two shapes x and y , sharing a prefix means that x begins with y , or y begins with x ).

More complex uses of the rank operator can control how the verb will split up arrays to determine agreement.

The rank operator has a few different ways of being used, but for now I will consider the most basic cases, where there is a verb on the left and a noun on the right.

The noun given controls the verb rank of the verb it modifies, producing a new verb with the specied rank.

That was a lot of usage of the word “rank”, so let’s consider some examples.

NB. An array of shape 2 3

i. 2 3

0 1 2

3 4 5

NB. An arrray of shape 2

10 20

10 20

NB. 2 is a prefix of 2 3, so these arrays agree, and can be broadcast

10 20 + i. 2 3

10 11 12

23 24 25

NB. What if we had an array of shape 3?

10 20 30

10 20 30

NB. Now this does not agree with i. 2 3

NB. However, we can see a way it could

NB. if we added it to each rank-1 member of i. 2 3 instead instead of as a whole

NB. This is what the rank modifier solves

10 20 30 +"_ 1 i. 2 3

10 21 32

13 24 35

NB. The left rank here is infinity - take the array as a whole

NB. The right rank here is 1 - chop the array into lists first

NB. This concept generalises to arbitrary ranks, too

NB. A table

100 * i. 2 2

0 100

200 300

NB. A brick

i. 3 2 2

0 1

2 3

4 5

6 7

8 9

10 11

NB. Add all of x to tables of y

(100 * i. 2 2) +"_ 2 i. 3 2 2

0 101

202 303

4 105

206 307

8 109

210 311

NuVoc links: i. integers, + add, " rank.

Rank can be a tricky concept to understand, but it is an extremely useful one when you do—so much of J revolves around it.

Mathematical primitives and verbs

These are great for small puzzles.

Want prime numbers?

p: primes will give them to you.

J also gives you access to complex numbers, polynomials and their roots, prime factors, and hypergeometric trigonometric, and hyperbolic functions as primitives.

The standard library also has calculus facilities—J can find the derivative and integral of a lot of verbs, including user-defined ones.

Very handy to have.

Obviously other languages have a lot of these features too, but things like having easy access to primes and polynomials from primitives is invaluable for some kinds of problems.

The things I don’t like

Some parts of J are a huge pain.

While not dealbreakers for me, they add more of a faff than should be present in a modern programming language.

As with above, these are listed in a vaguely decreasing order with the most annoying parts first.

In my opinion the more serious of these should be fixed outright.

Importing files

This is hands down the worst part of writing J code with a multi-file project. J imports files from the current working directory. This means that if you have a script that loads another in it, the working directory that script is run in will cause it to either work or crash.

J does have a workaround for this: jpath .

It provides a way of referring to certain system paths that you might use a lot.

For example, ~Projects/md/md.ijs might resolve to /home/ibzan/j903-user/projects/md/md.ijs .

The problem with this approach is it still relies on an absolute path effectively—just trading /home/ibzan/j903-user/projects for ~Projects .

Requiring all J code to be installed in a specific location is the behaviour I want to avoid—while less bad for referring to separate projects, it means code within the same project must know where it is installed!

I strongly believe that file imports should be relative to the directory the script is in. For the most part, this is what you actually want as a user!

I ended up having to write a project to work around this issue. You can find it here. Although only a bit of work, it is vastly more obtuse than should be necessary.

Exceptions

J has exceptions. I do not like exceptions in the first place, but within J it feels like the best compromise for signalling errors. The type system is not rich enough to support option or result types, and errors are generally rare at “runtime”—more often than not they are effectively programming errors. Many exceptions are closer to compiler errors than runtime exceptions, since J is an interpreted language.

There are still potential runtime errors, such as incorrect datatypes, invalid inputs, memory errors and such, but they are typically not an issue for the scale I work at.

On of my main gripes with these exceptions is how vague they are, which doesn’t help working out what the problem is. J assumes that the programmer is already familiar with the rules of J and can determine what is wrong with a phrase. For a new J programmer, the errors offer practically nothing of value to aid understanding. Some of the simpler ones are alright: a domain error means that the domain (input) is incorrect. This is most frequently an incorrect type, but could also be an incorrect number of arguments.

'a' + 'b'

|domain error

| 'a' +'b'

1 *: 2

|domain error

| 1 *:2

However, when this is embedded within a larger phrase, it can be difficult to ascertain the issue.

J also uses spacing to indicate where the problem occurred rather than leaving the phrase formatted as the programmer did and annotating it. I believe this is because the original format is discarded during the tokenisation step of interpreting.

J’s dynamic scoping means that it searches for a name whenever a private scope is executed. If J cannot find the corresponding object (whether it is a noun, verb, conjunction, etc.), it signals a value error:

f =. {{ g y }}

f ''

|value error: g

| g y

In this case, J was able to provide the programmer with some additional information: g is the missing value.

However, many other errors don’t include any such explanation.

This is mostly a pain when dealing with swapping between interactive development and development within a script.

It can be easy to overlook a particular definition and have to search back through the input log to find how some verb was written.

It may be clear from these last two examples that J exceptions aren’t hugely informative. Without enumerating other classes of errors that are signalled at runtime, these Considering the state of compiler error reporting in languages like Rust I think there’s little excuse for not improving J’s description of errors.

It isn’t too hard to imagine some of the improvements that could be made to some of these errors. Returning to the domain error, it would be trivial for J to report that the number of operands was incorrect:

1 *: 2

| domain error

| incorrect number of operands

| *: requires one operand

| 1 *: 2

| ^^

E. 'foobar'

| domain error

| incorrect number of operands

| E. requires two operands

| E. 'foobar'

| ^^

When operating on incompatible types, an improved error could also be easily reported:

'a' + 'b'

| domain error

| incompatible noun types

| + requires numeric nouns

| 'a' + 'b'

| ^

How about a length error, when two array have incompatible shapes?

1 2 3 + 1 2

| length error

| x shape: 3

| y shape: 2

| 1 2 3 + 1 2

| ^

1 2 3 4 + i. 3 4

| length error

| x shape: 4

| y shape: 3 4

| 1 2 3 4 + i. 3 4

| ^

The error could even go further as to explain what agreement is.

This quick experiment in working out a better format shows, in my opinion, how easy it could be to fix this glaring issue.

Documentation

J documentation is often sufficient or very good—especially with primitives and core language concepts—but sometimes lacking. In particular, descriptions of addons are frequently missing or equally terse as the language itself, which doesn’t aid readability when looking for a detailed description. The lack of an easy way to search the contents of addons makes them hard to adopt.

A recent example—I needed to copy a directory to a new location.

I expected that this would be a foreign, which is where file copying is.

Nope.

I tried implementing my own, but it caused the interpreter to segfault.

Not wanting to look into it too much further (it was really a small part of the project), I settled for invoking cp -r on the command line.

When writing this article, I found out about the general/dirtrees addon, which has this feature.

I was surprised that this particular functionality wasn’t included in the standard library, but at least it is an addon.

The lack of clear documentation for addons severely hinders their usage. I think a real priority ought to be completing the wiki with missing contents and explanations for each addon.

String operations

This is an artifact of using the flat array model to represent strings as rank 1 arrays. In the flat array model, an array cannot contain an array. Since strings in J are actually just arrays, they can either be a higher rank (a rank 2 string is a rectangle of text, probably with padding characters) or boxing each string, which converts them to atoms.

To avoid padding strings with unwanted spaces, it’s necessary to work on boxed strings instead. These can be different lengths without adding padding characters.

The downside, however, is that boxed data is more awkward to interact with. Primitives do not go into boxes; they operate on the box itself if applicable. This means that when dealing with an array of boxed strings there are two options.

The first option is to use " rank to run a verb over each individual box, and start by unboxing with > open.

This approach is only viable when the final results can be combined into an array with either acceptable padding or no padding.

For example, to convert an array of boxed strings to their lengths, as an array: #@>"0 , using @ atop and # tally.

When the desired operation does not reduce the string to a suitable shape, or when padding characters are to be avoided (as is often the case), instead one must use &. under (dual) with > open to open each box, apply a verb, and then box the result.

To convert each string to upper case, one might write toupper&.> , using toupper from the standard library.

The adverb &.> is so common that it is also included in the standard library: each .

The problem with each of these approaches is the added complexity in what would hopefully be a simple operation. Given the constraints of the array model, it is understandable why this is the case, but it does complicate text processing in my experience.

Numerical codes

This is a minor one.

J does not like to use reserved words at all.

Most things that other language would use as keywords are implemented as standard verbs in J.

Instead, many common functions are implemented behind a primitive with some numerical codes.

The few words that J does use are all suffixed by a . to indicate at the parsing stage that they are keywords.

Take trigonometric functions, accessed via o. circle functions.

Instead of names, they are accessed by a numeric code as the x argument to o :

sin =: 1 & o.

cos =: 2 & o.

tan =: 3 & o.

arcsin =: _1 & o.

arccos =: _2 & o.

arctan =: _3 & o.

The workaround is exactly as above: create aliases to the verbs.

There is also the math/misc addon which contains a script ( trig.ijs ), which defines these aliases.

This is most prevalent with J’s foreigns. Foreigns are what J calls access to system functions, like reading a file or getting the current time, and some miscellaneous functions, like debugging controls and some things that don’t fit into primitives.

All foreigns are addressed as a pair of numbers and the !: foreign conjunction.

This ends up being quite hard to remember in my experience—I prefer having names to numeric combinations.

As with above, assigning names myself or finding an appropriate addon will help, but is a bit tedious to repeat.

The once cases where I have found numeric codes acceptable is within the ;: sequential machine primitive.

The state transition table uses a numeric code to determine what action to take in each state, given a certain input.

Since the state transition table is often quite large, the shorthand of a number instead of something longer is beneficial.

One of the other changes I would make (namespaces) would allow for more elegant solutions to this issue, by storing all of these values in sensibly-named namespaces. Locales could also work here. Not a huge problem, all in all.

What I would change

These are the changes I would make to J but are probably too big to be changes to the current language. They would likely require a large breaking version, or a successor language that is inspired by J.

Lexical (instead of dynamic) scoping

Most contemporary programming languages use lexical scoping. J uses dynamic scoping. Dynamic scoping is where the value of a name is determined when the code is executed, rather than when it is defined. In other words, the “most recent” definition is the one used. For example:

a =: 5

b =: {{ +: a }}

b ''

10

a =: 10

b ''

20

On the REPL, this is great.

It allows for fast iteration by constructing a verb out of two or three others, testing, and then tweaking one of the constituent parts and having that affect the final verb without having to redefine it.

As a result, you can spend far less time copy-pasting existing definitions without changing anything to just update the contents to their new versions.

However, in scripts this is often more of a pain than not.

If you want a verb to be accessible outside the script, it has to be globally accessible, but so do the verbs it calls.

This is because a private binding in J is only retained for the duration of the definition of its namespace.

After a script that defines a private name is finished, its private definitions are dropped.

Hence, a complicated script can export far more than needs to be accessible just so that it functions.

The current workaround is to use f. fix to recursively expand names, which prevents private definitions from ceasing to exist at the time the longer name is used.

The impact of lexical scoping on the REPL can be mitigated by changing the workflow. Instead of writing J code directly into the REPL at all times, the programmer instead writes to a script file which is then loaded on the REPL. After developing the next piece of the script interactively, it’s copied into the file which is then reloaded.

Special Combinations

This issue arises directly from dynamic scoping.

Each verb in J is executed right-to-left, without knowing anything about the verbs that executed before or after it. This is often useful, because it means the code being written is inherently pure. However, it can have performance issues, especially when some things could be terminated early, or intermediate products are not needed.

To tackle this, J has a lot of “special combinations”, which are basically special compound verbs the interpreter recognises to perform and performs a specialised function optimised for the example.

As an example, take ? roll and $ shape being used together to create an array of random numbers, with @ atop for the special combination.

NB. The standard library verb timespacex records the time and space used in

NB. a particular phrase.

NB. Generate a 3000-by-3000 matrix of random numbers from 0 to 99999:

timespacex '? 3000 3000 $ 100000'

0.053085 2.68437e8

NB. Now let's try using a special combination: ?@$

timespacex '3000 3000 ?@$ 100000'

0.041604 1.34219e8

The memory usage (second number) is better by a factor of two, because there is no need to create a copy of the initial array (3000 3000 $ 100000 ) in the first example.

Special combinations are recognised by the interpreter at the moment of verb creation. Since they are built out of a conjunction to combine different verbs together, the interpreter must recognise the precise combination at the moment it is created. A conjunction creates a new verb as soon as it is given both arguments. In order to do this, the contents must match exactly. And so:

roll =: ?

shape =: $

timespacex '3000 3000 roll@shape 100000'

0.053171 2.68438e8

This fragment has to create a copy of initial array because the interpreter has not recognised the special combination.

f. fix can be used here to convert a phrase to its primitive form, which allows the interpreter to detect the special combination.

timespacex '3000 3000 (roll@shape f.) 100000'

0.0413 1.3422e8

In a more ideal setting though, the names assigned to verbs would not interfere with this optimisation.

This is because the values of the names cannot be determined until the code is actually run, due to dynamic scoping.

Consider:

roll =: ?

shape =: $

randoms =: roll@shape

roll =: 0: NB. Constant 0 function

3 3 randoms 100

0

Lexical Scoping and Special Combinations

The change I would make here is allowing for lexical scoping. This would handle the definitions of those internal names lexically and then the user would be free to keep them as local definitions.

As I mentioned above, however, I really like dynamic scoping on the REPL. Potentially the best solution is to allow a mix of both, but this comes across as nasty. I think the added complexity of having mixed dynamic/lexical scoping may be too great for what it adds to the language.

After all, I am strong believer of the language not allowing bad things to happen in the first place. If something is possible to do within a language, however niche or not designed to be used, you can practically guarantee someone will use it. Usually, I’d say this is their own fault, but this one raises a lot of questions about how it would interact across scripts. If one script specifies it uses dynamic scoping and another lexical, how do they interact?

Can there be a compromise to allow both scoping approaches?

Possibly.

Scoping style could be configured when the interpreter starts and not allow it to be changed from within a session (although one might expect a foreign to do this).

This would allow a REPL to run with dynamic scoping, and a file to run with lexical scoping.

The difference between developing interactively in the REPL and within a file may prove unintuitive, though.

To conclude this section, I don’t think there’s an obviously good way to support both dynamic and lexical scoping. This is almost certainly why no language I am familiar with do both and settle on supporting only a single one.

First-class verbs

Verbs in J are not first-class values; they are special objects that cannot be passed around as data. This leads to the distinction between verbs, adverbs, and conjunctions. In a language with higher-order functions and first-class functions, J’s adverbs are simply higher-order functions.

This change would also remove the need for gerunds in the language for dispatching separate verbs.

Instead, the programmer could construct a list of verbs and select the appropriate one (with say { from) and then apply a noun to it.

Why is this change needed?

In my opinion there are a few motivating reasons.

Messy Representation

When a verb in J is given a name, it is not actually stored as an instance of the verb (which would be possible if they were first-class).

Instead, it is passed around as the name and turned back into the value as necessary.

The adverb f. fix can be used to recursively expand names to convert a definition into one made of primitives only.

Furthermore, a gerund created with ` tie is actually stored as an array of boxed strings.

The representation of a verb with names in it in the meantime is not ideal—although unlikely, something that is not a verb could be recognised as one if used in the wrong scenario. Ideally, I think this should be cleaned up to prevent it from being possible in the first place.

Rank Mishaps

Currently, the behaviour of verbs and their names can cause unexpected behaviour for even experienced programmers. This is from a property of verbs and a property of names.

In J, verbs have a rank. This fact is so important that every page on NuVoc includes “WHY IS THIS IMPORTANT?” which explains why the rank of a verb matters. The rank of a verb determines the maximum rank that a verb can operate on. A higher rank input array is subdivided into arrays of a rank the verb can handle. As covered in the leading axis model section, this has advantages.

For example, the verb + plus has rank 0 0 .

This means that both the x and y input arrays are broken down into atoms, added individually, and then collected to the original shape.

Note that the leading axes of the operands must still agree—you cannot add incompatible array shapes.

By comparison, consider the verb # tally.

It has rank _ —infinity.

That means that it can take an input array of any rank whatsoever and produce an output without subdividing it.

This is because tally counts the number of elements in the first axis, so it can work on an array of any rank.

However, how J treats the rank of a verb is what leads to the weird behaviour. When a verb is assigned to a name, the name is also given a rank that matches the verb. However, if the verb is reassigned then the rank does not change. This is deeply strange. For example:

NB. Assign a rank 0 verb to f:

f =. +

f b. 0

0 0 0

NB. Assign f to g - g is rank 0:

g =. f

g b. 0

0 0 0

NB. Reassign f to something else:

f =. ,

f b. 0

_ _ _

g b. 0

0 0 0

NB. Now g is rank 0, but f has infinite rank.

NB. However, used monadically, g will resolve to , ravel - not + conjugate.

NB. This is because f is now , instead of +

NB. To demonstrate, let's use the close composition @ atop:

i. 3 3

0 1 2

3 4 5

6 7 8

<@f i. 3 3

┌─────────────────┐

│0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8│

└─────────────────┘

<@g i. 3 3

┌─┬─┬─┐

│0│1│2│

├─┼─┼─┤

│3│4│5│

├─┼─┼─┤

│6│7│8│

└─┴─┴─┘

Namespaces

Currently, J supports two kinds of namespaces: private namespaces, for definitions, and public namespaces called locales. Private namespaces are for all intents and purposes inaccessible to the programmer. They serve only to bundle together the contents of an explicit definition.

To me, locales feel very hacky to use—they are accessed by appending _localename_ to the name of something you want to access, where localename is the name of the locale.

This form is called a locative.

For example, after loading math/calculus , one must use deriv_jcalculus_ to access the deriv name it contains.

I think there are a few main issues with locales.

Firstly, J uses a hierarchy of locales to search through when resolving a name. This can quickly become convoluted with multiple scripts involved, which can load more locales into the workspace.

Secondly, locales are not first-class values (this is a common theme in J for things that are more complex than raw data). This causes the usual issues that arise from not being first-class: difficult or impossible to pass around between different parts of the program and requiring special syntax to construct or access.

Thirdly, executing a locative actually changes the implied locale to execute the verb.

That is to say, instead of accessing the value from the locale directly, J instead changes the search path and then looks up the name.

This behaviour can introduce subtle bugs into code that are hard to track down.

The only place I found this mentioned was on the page for f. fix which covers the problem and a solution.

I would change this by replacing locales with a new datatype: namespaces.

My namespace is a first class value that contains names, accessible via some primitive—while appearing similar from the outside, requiring explicit access into a namespace would prevent the above issues.

Precisely what symbol would be used for access I am not sure—something not already used would have to be picked, which rules out something common like . or :: , and J’s syntax doesn’t support -> .

Of course, in a hypothetical successor language this would be designed from the ground up instead of being retrofitted into the existing specification.

I think this would be an overall benefit, allowing for a more sensible approach to grouping names together. It also prevents namespaces from having to be manually freed by the programmer, which is something J does not expect you to do with most data.

2-train for function composition

This is a change that was eventually adopted by Roger Hui, one of the main developers of J.

In short, this change replaces the meaning of the 2-train (v u) with @: at instead of hook.

I think this would generally lead to code that is easier to read, and a conjunction isn’t a huge price to pay for still having access to the hook, which is a very useful combinator at times.

Within array languages, the 2-train as hook is an oddity of J’s. Most other array languages treat a 2-train as composition of some form (J has four composition conjunctions).

In the meantime, the composition conjunctions and a capped fork ( : v u , with [ [: cap) are both available for composition.

I use both of these forms from time to time—in fact md uses both capped forks and composition conjunctions, based on the situation.

The hook is then moved to its own conjunction—such as h. in J, as Hui suggests—and used as a normal modifier.

This would also allow for both a “forward hook” and “backward hook”, an idea shamelessly stolen from BQN.

For example, f h. g y could be equivalent to y f g y , and f H. g y could be equivalent to y g f y , with similar for the dyadic case.

Any backward hook could be written as a forward hook, however I believe there are scenarios where one would be clearer than the other based on surrounding context.

Given the ubiquity of function composition however, I believe that the terser syntax leveraging the 2-train is superior and would help to reduce the noise present in a lot of tacit definitions.

Unicode

By default, J treats strings as a sequence of bytes (the same way C does, which the J interpreter is written in).

However, a large amount of text these days is represented as Unicode.

J does have support for Unicode—the u: Unicode primitive provides conversions to and from Unicode.

J could be changed to support Unicode by default for strings, which would simplify dealing with modern text.

This isn’t a huge problem (IO verbs can be created that handle UTF-8 instead of ASCII), but a bit of a faff to have to handle manually.

Mostly, this is an artifact of the age of the language.

Mutation

As a preface to this section, I love immutability.

It prevents classes of bugs from existing and makes data easier to reason about.

It’s a good fit for a language like J that is “data-oriented”.

Sometimes, however, mutability can be important for performance.

There are certain algorithms that just perform significantly better when written in a mutable fashion.

J does not provide easy ways to mutate a data structure. This is because J is built on the observation that when modifying an array, most of the work is in calculating the new data, and little of the work is in writing it into memory. This works very well for large arrays and when performing a whole-array modification, such as arithmetic or calculating some rolling value. It also prevents race conditions, since a shared array will not be mutated by another region of code. When modifying a small number of values in a large array, however, this is very inefficient. Another case where mutation would be suitable is when working with a temporary array that is only used to work out the final result. In this case, it is probably not shared and does not need to have its first value retained.

J does support a limited form of mutability in the form of assignment in place.

This is possible when using a particular adverb ( } amend), and only of the following particular form:

name =. x i} name

or slight variation on this.

Using this special combination avoids creating a copy of name and instead mutates the array, and it is implemented as a special case in the interpreter that recognises this pattern.

In addition, appending another array is possible in-place via name1 =. name1 , name2 .

Modifying a single element of an array is less prevalent in J than other languages, since every operation that the user cares about can be broadcast across an array to act on it as a whole.

Verbs can also be modified with " rank to affect different rank subarrays, which makes manual iteration for modifying an array pointless.

This combination of factors means that the ability to edit single elements is unneeded.

In those cases it would be nice to specify that the interpreter is allowed to mutate by reassigning to the same name.

However, some data structures do not fit into arrays. Trees, for example, are often not represented well in an array (you could represent a tree with an adjacency matrix). J does not support mutation of boxed data structures like this, and each change requires the whole structure to be copied.

Adding a limited form of mutability would help this. The place where it makes the most sense is within the private namespace of a definition. Here, multithreading aside, the interpreter can be sure that no other bit of code will have access to a given value and rewrite its contents in place as much as it likes. To demonstrate, consider the following:

u =: {{

NB. This has to copy, since y starts as being external to u's namespace

y =. +: y

NB. Since we made a copy, this namespace now owns y and can mutate it

y =. *: y

NB. Any operation that doesn't change the datatype or shape of y can mutate in place

y =. -: y

NB. When y is returned from the verb, it is given to the parent namespace and treated normally

y

}}

NuVoc links: +: double, *: square, -: halve.

In this example, the interpreter would have to read ahead in the direct definition to know that it is safe to mutate y .

I will admit it is a slightly contrived example: this could be expressed as a single tacit verb -: @: *: @: +: , using @: at to compose the individual verbs, however the general point holds true for a more complex direct definition.

The fundamental idea is one of ownership: values are passed by reference, but any copies made are owned until they are used in more than one place.

This allows for the interpreter to manage its memory far more precisely.

Another option could be to create a data structure that explicitly allows mutation, like Clojure’s transients.

Affine character arithmetic

This feature is directly lifted from BQN. It’s simple, but brilliant.

Treat characters as an affine space. An affine space is a space that allows three operations:

Find the difference between two elements

Add a quantity to an element

Remove a quantity from an element

Crucially, the ability to directly add two elements is missing.

This prevents C-style 'a' + 'b' (which is 195 , by the way), but allows for 'a' + 1 == 'b' , 'b' - 1 == 'a' , and 'z' - 'a' == 25 .

Want to parse a grid of digits?

You can write grid - '0' .

Rotating characters?

You can just add and subtract as necessary, handling boundary conditions.

I find this far superior to J’s approach.

It avoids the extra conversion needed to and from a numeric datatype.

For J, you have to use a.&i. which finds the i. index of the given character within the a. alphabet.

Under some circumstances, you can avoid converting the characters to integers and keep them as bytes with the special combination &.(a.&i.) with &. under (dual).

For Unicode, it can be converted to a number using 3 u: 7 u: ] ( u: Unicode) and manipulated the same way, using the codepoint as a number, but the conversion cannot be avoiding owing to the nature of the UTF-8 encoding.

While both of these work well, the extra work required to convert back and forth between the two representations can be noisy.

This would also discourage using things like 97 to represent a.i.'a' (the byte value of the character a ), which I believe is a benefit.

Conclusion

First things first, congratulations are in order. Congratulations for making it this far. Thank you, dear reader, for indulging me for as long as you have. I hope you have found this post interesting.

J, and array languages in general, offer a very interesting paradigm for programming in. I highly recommend learning an array language such as J, APL, BQN, or K, if you are interested in learning more about different styles of programming and ways of tackling problems. As a tool for quickly developing algorithms, I find J to be an excellent tool to have at my disposal. It provides the tools necessary to write code quickly and is efficient for getting ideas from concepts to a working example. Understanding concepts like rank can really help formulating solutions to array-like problems in general, and array languages will guide you towards that as you use them.

The syntax adopted by J has strength in its brevity (albeit this can be a double-edged sword), although it has its flaws. Lack of operator precedence makes well-written code easy to follow, but there is a large initial learning curve involved when encountering new primitives. In addition, poorly-written code can be very difficult to read for newcomers. Invisible conjunctions do not aid this, either.

The advantages of a minimalist type system bring drawbacks with them. Chiefly, composite data types like records and structs are missing. This makes sense when you view the equivalent data structure in J as a collection of columns, not rows, but can be annoying when data processing needs to think about rows. Furthermore, more advanced types, like unions, are also missing. They really open the door to more advanced programming in areas like error handling, in my opinion, so J is stuck with exceptions for now. On the other hand, for its core purposes, advanced types aren’t necessary. When it comes to crunching numbers, the underlying representation is sufficient.

J is missing some of the nicer features common in more recently-developed languages, and especially some of the rough edges can be annoying to have to deal with. In particular, scoping and file importing are pretty nasty in my opinion. There’s not much of a chance of J changing fundamental parts of it like this, though, so the onus will be on newer array languages like BQN to improve on these shortcomings.

Ultimately, J was a language that was 100% worth me learning, and I encourage anyone looking to learn new approaches to programming to learn an array language.